I previously wrote about how the failure of Washington’s real-time seed-to-sale traceability tracking capability had enhanced the ability of licensees to break the rules. Doing so became easier and less risky. Today, the ongoing dysfunction in the regulated market caused by the premature roll-out of LEAF is interfering with some wholesalers’ ability to legally sell their product. This is increasing financial pressures on an industry that is already, on average, struggling. Most licensees that I know seem to be decent, honest, hardworking people. They also seem to be aware of the dramatic declines in average prices within the regulated system and the even larger premiums allegedly being paid for some of the product being sold outside of Washington or being sold outside of regulated channels inside Washington. This post does not discuss whether diversion IS occurring … it just describes some ways in which it COULD be occurring.

The Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB, or LCB) would have it be known that DIVERSION is not a problem in the state-legal cannabis market they regulate. This post sheds light on how, for their assertion to be true, LCB oversight and enforcement efforts would have to consistently succeed across many different points of possible diversion. Either that, or the honest and hard-working licensees of this industry would all have to be uniformly law-abiding, rule-abiding participants of that industry.

When one hears the LCB speak of diversion, it often seems that they mean instances in which product flows out of the regulated market in ways inconsistent with the laws and regulations they enforce. Such instances are, according to the LCB, uncommon. They say that, through their partnership with the MJ Freeway/LEAF software development team, the compliance-reporting1 system rolling out over the next few months has virtually eliminated the threat of such unreported and possibly untaxed transfers of product.

Such flows of product OUT of the regulated system will be the focus of this post. This is the class of diversion that I will refer to as out-diversion.

Recently, the LCB communications directorate released information to forestall concerns that the virtual breakdown of the new compliance-reporting system might increase the opportunity for such diversion to occur. We were reminded that all necessary pieces of information continue to be gathered, and that local records must still be kept by licensees and that video footage of everything still exists2 and that enforcement officers can be anywhere at any time when they are not otherwise occupied busting patient/farmer exchanges.

They’ve got it under control. There is nothing to see here, folks … just move along, please. The public position of the regulators is that no such diversion is occurring.

Before I dive into the many possible flavors of out-diversion, I’d like to briefly discuss two other classes of diversion: in-diversion and intra-diversion.

In-diversion is any instance in which product inappropriately enters the regulated system (be that at the level of the farm, processor, transporter, lab, or retailer and whether it happens with or without the involvement of the regulators or their enforcement staff). I will not cover this class of diversion, other than to emphasize that it’s potential benefits include the ability to augment the constrained genetic set available to the regulated market, offering a source of product for post-processing or direct sale that is not constrained by the regulatory framework which constrains regulated wholesalers, and offering a flexible means of pulsing production capacity. Hidden instances in which wholesalers and retailers were vertically-integrated would clearly be beneficiaries of this class of diversion (and product “white-labeling” would be a useful tool in such efforts). The existence of in-diversion would result in a subset of the product flowing through the regulated system being, technically, non-regulated (what I will call “apparently-regulated product”).

Intra-diversion is any instance in which apparently-regulated product inappropriately flows between producers, processors, transporters, labs, retailers, regulators and/or legislators. For example, cases where wholesalers send flower QA samples weighing one ounce or more to labs and where the labs report that all 28+ grams of that flower were consumed during testing are an example of intra-diversion. Product (or other things of material value) flowing to regulators, enforcers, or legislators in inappropriate ways would be another example of intra-inversion. Excessive use of educational and/or bud-tender samples, many deals where raw material is processed by processors not affiliated with the producer and mixes of product and cash “pay” for the processing, and multi-store retail chains balancing inventory across stores would also serve as examples of intra-diversion. In general, any “payments in kind” using product are likely examples of intra-diversion (and something the LCB refers to as “direct money’s worth” in Enforcement Bulletin 15-02).

Out-diversion is any instance in which apparently-regulated product inappropriately flows out of the regulated system. Two types of out-diversion that stand out in the rhetoric of the LCB (and the DOJ) are the diversion of regulated product across state lines and the diversion of product to minor children for reasons other than medication. Washington’s is a market where over 1,200 farms are supplying about 400 open retail access points which are, themselves, increasingly geographically clustered in those areas that will allow them to operate.

Data have suggested, since the second year of this market, that retail sales volume has consistently lagged increasing production levels. Recent data suggest that levels of inventory held at wholesale are increasing and that the motivation for out-diversion has increased dramatically (see related post on HI-Blog here).

The current imbalance between the chokepoint of retail access and the increasing tendency of new businesses attempting to offset low prices through increased production leads to ripe opportunities for out-diversion. These opportunities are particularly ripe now that wholesale prices of product in other states are often 4-6 times what they recently were in Washington.

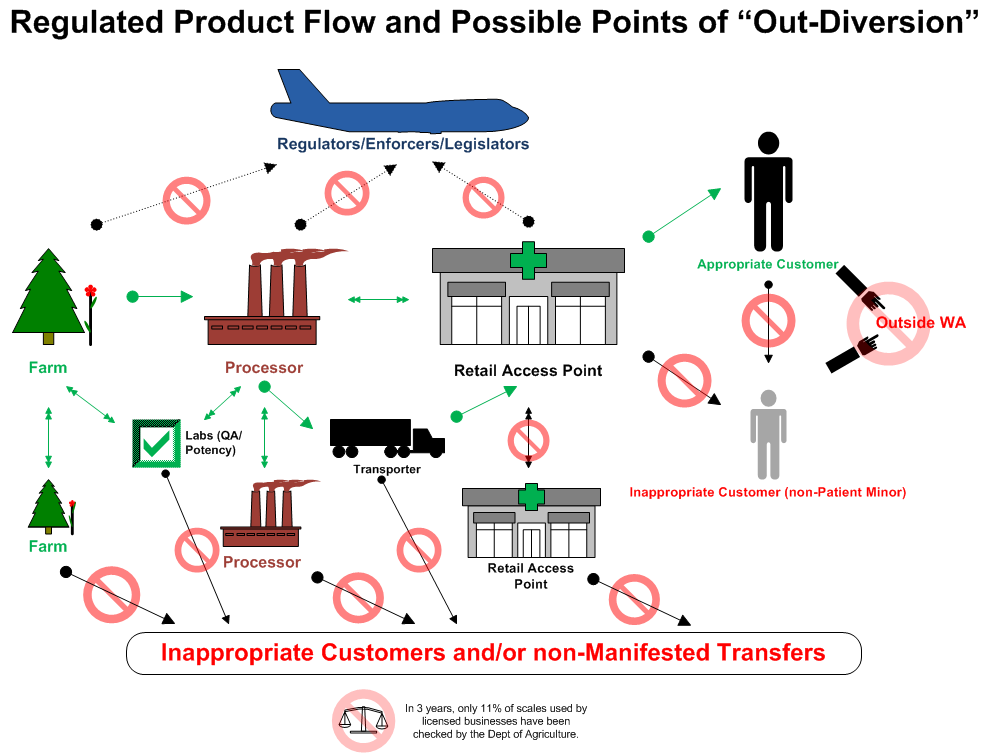

To efficiently communicate the myriad points of potential out-diversion, I compiled a graphic showing product flows (the arrows) within and out of the regulated system. The tree/flower icons represent farms, the factories represent processors and the green-cross storefronts represent retail access points. Transporters are represented by the truck and the Labs are represented by the checkmark. Flow amongst farms and processors is indicated by the smaller second row of icons. The LCB and Legislature are portrayed far above the market they define and control as an airplane (to reflect their 30,000-foot view of things). Consumers are the people to the right. Product flow within the market tends to move from left to right.

All points of potential out-diversion that seem reasonable have been highlighted by the hazard icon (the red circle with a diagonal slash). Note that I indicated out-diversion to “inappropriate customers and/or non-manifested transfers” as coming from the 2nd row of farms, processors, and retailers. This was just to avoid arrow density — such diversion could just as well come from the primary producing farm, the initial processor and/or the retailer. It could also come (indirectly) from the airplane, if the regulator/enforcer/legislator(s) in question were serving as middle-people in a product-movement scheme. I did not include that arrow, as I wanted to stress the fact that any and all flow of product (or cash or promises or business interests or lease payments or whatever) coming from regulated (or certified) players in the industry TO the airplane are wrong. Many thanks to Governor Inslee for his veto of the anti-sunshine bill that would have helped keep such Legislator involvement secret (if it were occurring).

Many points of potential diversion into, out of, and within Washington’s regulated cannabis market exist. The virtual meltdown of valid traceability reporting comes at a point in time where price declines, sales declines, a supposedly huge fall harvest, and a growing awareness of the revenue potential of selling either out-of-state (whether directly or indirectly) or within-state in a manner that skirts the constraints of the regulated system have all arisen.

It is not just a compliance reporting app that is failing, it is established and newly-designed workflows(that worked yesterday) and repeated re-work and frustration for licensees and the ongoing negative impact on licensed businesses that show that the regulators are failing in their mandate to ensure a functioning market able to adequately serve the needs of Washingtonian consumers while at the same time inhibiting non-regulated sales and all of the bad things that supposedly come along with those.

If the LCB should ever be able to supply detailed “supply chain” data covering the post-BiotrackTHC days, perhaps we will eventually come to know how much of the potential for diversion is being realized. With the data made available and being collected (or not) today, we cannot know with much certainty.

In truth, I doubt that the LCB can, either.

————————————————————-

Footnotes:

1 “Compliance Reporting” is the phrase LCB Chief Information Officer Mary Mueller recently used to describe the virtually non-functional LEAF traceability solution that was rolled out on Feb 1 to a fanfare of failure. By attempting to re-brand LEAF’s $3,081,000 effort to replace BiotrackTHC’s Seed-to-Sale Traceability System as a “compliance reporting” system, the LCB is attempting to lower the bar of expectations regarding system requirements and thereby avoid another in a series of system development failures.

2With approximately 500,000 hours of such footage being recorded daily, it is unlikely that the LCB, given their current levels of staffing, are keeping up with those recordings. A good deal of signal could easily be hidden in all that video noise.

Jim,

Excellent work as always, I just posted your diagram and a link to this article on Instagram. Ever since we stopped growing for 502, around a couple months ago now, we have been out of the loop as far as what is going on with the technical aspects of running the business. I was contacted by a supplier of organic products and beneficial insects for 502 growers last week who mentioned that the LEAF system had made it impossible for growers to make legal sales for a week recently and that it was the straw that broke the camels back for some folks who were already struggling. Apparently there was a recent meeting of some of the smaller players in the industry who have been fighting their hardest to make a good and clean product in this broken market and at that meeting, the potential for legal actions against the state was discussed. It will be interesting to see how things go forward as more and more evidence comes to light about how broken and dirty the market is, I find it hard to believe that the state can pretend that they are unaware of what is happening for much longer- just to save their butt from legal actions against them, or having to spend more on oversight and enforcement.

Thanks for all your well-researched and thoughtful posts on this troubling market,

-Bjorn

I appreciate your kind words, Bjorn.

This article is mainly speculative. I’ve certainly been looking at the small amount of data that remain describing the market … and even those suggest something is going on like this market has never experienced before. Folks must really be suffering … or the data are bad. Unfortunately, there is no good way to say with certainty right now.

I hope you are able to pursue your goal of growing regulated cannabis in a well-regulated market at some point in the future. Clearly, lots of change on the part of the LCB (or whoever ultimately assumes responsibility for regulating on behalf of consumers in this market) would be necessary in order for that goal to be achievable in Washington.

All the best.

Diversion. It certainly is occurring. I am commenting merely to echo the comment regarding the “struggling” market. I have spoken to some of the producer/processors (large and small), labs and retailers regarding the health of their businesses. The producers, in general, seem to have the notion that the retailers are cleaning up financially. After my (only) one year in retail, I don’t see retailers cleaning up. The labs certainly aren’t making any money if they are actually doing the tests. Producers large and small are fighting for life. By and large the only entity making consistent money is the state. Many 502 businesses are on the brink of collapsing. Some went out of business during this leaf failure. I have intentionally spelled that business name without making it a proper noun. It has been a disaster. It has cost many businesses an untold amount of money. It left many good people dead in the water. Yet we all, from producers to retailers and labs are subjected, directly or indirectly, to the insane taxation from the state without representation or accountability. They brought us this leaf disaster. I mean come on, where is the enforcement, traceability and accountability from the state for this insane tax? There has to be someone reasonably educated in the government who should be able to see how close to the abyss 502 is due to the over taxation. Over taxation is the root cause of diversion. It’s a shame that we can’t short this market. BUT pay your taxes, regardless if the state deserves it or not. For once I’d like to see everyone in this 502 fiasco seriously get together and protest the madness of this system from a truly united front.

In case there is some disconnect, retailers pay 37% excise tax plus sales tax (close to 9%; 46% total!!!) on every sale. So when I hear people bitching about retailers and their “multiples” on mark ups, understand it’s an offset for this insane tax in this system which pimps all stakeholders out. The economics are clear. Retailers work almost half (46%) the day to pay the man. We are all set to slit each other’s throat to pay that man. Retailers negotiate the producers down so that they can cover the tax and possibly make a profit. The producers negotiate the labs down because they perceive testing (and public safety) to be too expensive. We’ve all seen the laboratory “numbers” shenanigans which create the lab “lie or die” scenario. The only consistent profiteer is the state. Just out of curiosity, who is responsible for the businesses that went under during this traceability fiasco?

We are competitors by and large from whatever sector of 502 we reside, but we really need to unite for real. We better consider standing together and holding the state accountable or we all face annihilation, not by each other, but by the profiteering entity that strives to keep us divided. So when we do nothing together and 502 collapses, what epitaph will describe your business? Do we have enough labs, retailers and producers in the state? Of course. We have (according to 502data.com)1293 producer/processor licenses, 442 retail licenses, and 16 labs (2 suspended). There are too many in every category to ensure a healthy marketplace. I get free market blah blah blah, but this is a rigged game. Some will survive, many will go under and many have already gone under.

So some producers are surviving by diversion. Some labs have survived by bullshitting numbers. If any stakeholder who has followed the “rules” is still standing, well then good for you. Who is responsible if the state is out of compliance? The number one tenet of the LCB is to ensure consumer safety. Have they ensured safety? Have they ensured compliance with all that tax revenue?

P.S. End user safety. Really? Can anyone really believe that pesticide testing isn’t mandated in 502? Safety for patients? What? I thought you said tax dollars. Has anyone seen the data from the state’s secret shopper program? That is a GREAT public records request. I encourage everyone to seek those data.

Wow, Jason!

I tend to agree with what you say … and love your description of the competitive cannabis-testing lab market in Washington as being a “lie or die” environment.

I’ve just finished some work on “Lab Shopping” by wholesalers (using traceability data through September as I still don’t trust the completeness of the October data I’ve received).

As the lab-shopping work dives into patterns of wholesalers moving their testing business to different labs over time, it also sheds some light on the migration of testing that occurred in response to the lab suspension that occurred last summer.

The pattern of testing “migration” that emerges in August and September shows pretty clearly that some labs got more than their “fair share” of the closed lab’s business.

Very interesting stuff. I should have some of the results of that work posted this week.

Regarding the “Secret Shopper” pesticide work being done by the Dept. of Agriculture and the LCB: I have looked at some of those data, and believe that Nick from Confidence recently presented some work he had done that showed not only the rates of “bad levels and/or bad pesticides” in flower and concentrates being flagged by the SS, but also those that had been seen in regulated product being tested in their commercial lab. The regulated numbers were lower than the secret-shopper ones (no big surprise), but they were still disturbingly large.

If I remember correctly, the failure rate of concentrates tested by the Yakima AG lab was either just below or just above 50% (I keep thinking 46%, but don’t remember precisely). I recall flower failure rates in the 11-25% range (again, not sure of those numbers).

The way both Agencies seem to be handling public records requests makes figuring out whose product was being tested (and where it was purchased) impractical. If anyone finds a way to merge their internal ID with a licensee UBI or license number (or finds a way to ask that they are fully responsive to) please let me know.

Thanks again.

Jim,

I know a guy who has a public records request in for the business names to go with the codes for the State’s secret shopper tests and some testing at farms that the state also did, I will let you know if he gets anything back. I have a large number of test results from the WSDA that were preformed on material from stores and onsite at grows, I was told that it was the 300 secret shopper tests, but if it includes all that, it also has other testing as well. Currently I have only looked through perhaps 2/3 of the testing results, 75%+ of the results are positive for forbidden pesticides. The tests which were clearly preformed at farms, have almost a 100% positive rate for forbidden pesticides/fungicides, my favorite foliage test was positive for 5 forbidden products. The farms where the tests were preformed must have been known offenders since their failure rate for everything tested at farms is so high. I have been researching the potential health effects of the forbidden products found in the tests and they are quite alarming, especially when you see how many fail for multiple toxins. I don’t think the situation could possibly any more of a mess and I advise everyone I know to not purchase recreational products unless they are 100% certain that the producer or processor where it originates can be trusted.

Hopefully someday rec isn’t a wreck,

Bjorn

Thank-you, Bjorn … I’d definitely be interested in anything that would help cross-reference the Dept of AG lab test identifiers with the licensees involved in producing the product. It is a bit of a stretch to believe that the LCB and/or the Dept of Agriculture would design their Secret Shopper program in a way that blinded them all to who was responsible for producing the samples being tested.

Scary summary of the results you’ve seen. The sample size looks to be consistent with the number of tests they were saying they had done through last fall or so.

I hope you have mis-interpreted them.

Cannabis available at a regulated store is supposed to not be harmful to consumers. It is generally held that cannabis, itself, is quite safe. It is also generally held that those pesticides and fungicides and other things that are toxic are unsafe.

Let’s hope you are wrong in your summarization.

One possibility is that AG is looking at a much broader swath of potential toxic chemicals than the commercial labs test for (not that that makes me sleep any better at night).

Jim,

I hope for the consumers sake that I am wrong as well, however, I wouldn’t be surprised at all if the vast majority of recreational product should not be consumed. I saw an article from NBC news in California from last year where they tested medical marijuana samples and 90% were tainted with potentially harmful products, if so many folks are willing to poison medicine to make a buck, I would imagine they would be even less hesitant about producing poison recreational product. I’m sure you have seen the not so cheerful test results coming from the Oregon and Colorado rec markets as well. I just received an email from a guy who says that he was poisoned by the sprays he was using at a big indoor grow here in Washington, sprays that they wouldn’t tell him what they were. Apparently he became very ill and still has many issues 2 years after the fact. According to this guy, he did research into the company and discovered that some of its investors were lawyers and people in the state government. It isn’t going to be easy fixing the problem of forbidden product use when the recreational market soup is so well mixed together with big money and the state.

-Bjorn

There are some regulated producers in this state that are quite clear and consistent in their public claims regarding what they do and do not use on (or in) their plants.

If you are fortunate to know and trust such folks, then regulated product that can be trusted can be had.

Seriously … if the only product on the shelves that says flat out that pesticides are NEVER used (etc., etc., etc.) costs a bit more, then it is up to the consumers (ultimately) to support that brand.

If, however, for consumers who are trusting labels and numbers on those labels (and the validity of QA testing that allowed the labelled product to be on the shelves), then regulated product that can be trusted is in they eye of the consumer.

With a strong, functioning, regulatory system in place, I suspect that such naïve consumer trust would be more justified.

It is a shame that the LCB won’t let that trusted Joe Camel fellow adorn labels in this state. I, personally, could never see old Joe allowing his face to be on pesticide-ridden and/or dangerous products. To be clear, I also trust Winnie the Pooh and the good Witch from the Wizard of Oz. I don’t believe either of them can be used in the regulated system here, either.

As always good job Jim

Thanks, Dana. I will be taking one final look later today at the “Lab-Shopping” data I’ve compiled and will likely put up a post late this evening or early tomorrow morning that summarizes my observations.

Lots of wholesalers show no obvious lab-shopping behavior (most of them, actually).

On the other end of at least a couple of scales are a relatively small group of (often very busy) wholesalers who show patterns of lab choice over time (coupled by reported potency results from the various labs used) that suggest they might be attempting to maximize reported potency levels. I have not yet bounced this stuff against QA pass/fail results, but that work is planned.

I will say one premature thing now about my observations in doing this work —- it is increasingly very clear to me that the lab marketplace enabled by the LCB and their sub-contractors is in direct opposition to the interests of Washingtonians (particularly the interests of cannabis consumers – be they recreational or medical).

There is a disturbing lack of consumer protection in the resulting regulated marketplace (not counting that supplied by conscientious farmers and processors — of which, I have no doubt, there are many).

That hurts the market. It hurts it today and it has the potential to hurt it even more down the road.

That is an unfortunate and avoidable shame.